We’re excited to share stories from scientists in their own words. This guest post is by Barbara Spiecker, a graduate student at Oregon State University (OSU). Barbara recently participated in a ‘Making Your Science Matter’ graduate seminar I teach each winter at OSU. Our staff, past and present, provide services such as graduate courses, seminars, and 1:1 coaching to their home institutions (e.g., National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis [NCEAS], OSU, and University of Washington) in exchange for office space. This year, I added a new element to the course – a capstone project. Students could choose to put their learning into practice in any form they liked – through websites, blogs, dance, radio, video, K-12 outreach. They blew me away with their passion, creativity, and willingness to share their why’s. Barbara created an inspiring video for More Than Scientists. Here’s her story.

—Karen McLeod, COMPASS’ Managing Director

I grew up in a humble town, thriving with flying hands and animated body language; in a home where I was truly normal; in a place where the fact that I do not hear did not require the slightest pause. I am Deaf, my family is Deaf, and I attended a Deaf school growing up. I was surrounded by people who sign, and I had full access to information through American Sign Language (ASL). It wasn’t until I left Rochester for graduate school that I first experienced living in an auditory world where my deafness was apparent, like an embarrassing pimple on a young me. In academia, I often missed small yet relevant talks about science among peers, or comments made by professors without the interpreters present, or seminars or videos that were inaccessible, to name but a few. On a daily basis, I missed valuable details, and over time they amounted to a gaping hole of missing information that I scrambled to madlib in my own time. It was exhausting. My blazing inner curiosity began to flicker.

When I learned about the science communication seminar that Karen and Bob Mason were offering, I jumped at the chance to take it. I had a personal stake in it. I knew I was not alone in struggling to access something as basic and humane as information. It is not people’s ability that is lacking, it is the connection. I cannot count how many times I have seen the faces of people of all ages brighten, sharing the same excitement I had at finally accessing and comprehending science content in their native language, ASL. I have become privileged, now a member of the so-called ivory tower as a marine biologist pursuing my PhD at OSU. I have entered into a position of power, armed with scientific knowledge. As a member of the Deaf community, I have a strong sense of responsibility to give back to the people who raised me and to share the powerful knowledge I have collected. I am also well aware it is not sufficient to just communicate science – one must also be able to elicit discussion about what we can do, given what we know. To effectively communicate science, one must have a special set of skills beyond just knowledge. I had the education, and I had responsibility; what I needed were the skills to think about relevance, dissemination, and discussion.

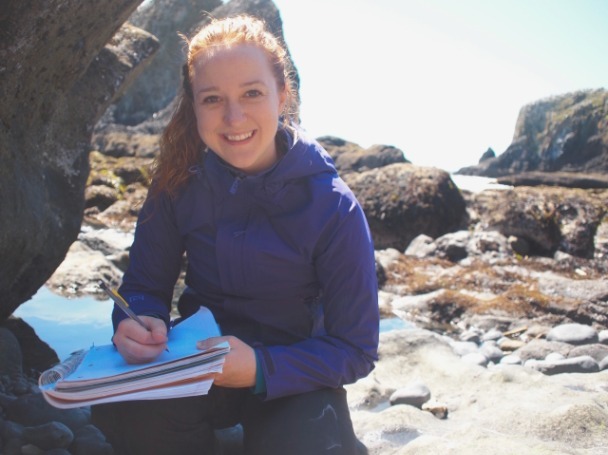

As I pondered what to do for my capstone project, I found myself sitting by my desk with countless research articles and blogs staring blankly at me from my computer monitor. A feeling bubbled up. In a sea of words and sentences, in papers and on the internet, we, I felt, had lost ourselves somewhere along the way – lost our voice and emotions, and most importantly, our physical being. The ubiquitous anonymous user plagues the internet. I decided to do something different. I made a video for More Than Scientists where I discussed why climate change is personal for me. I believed that my fears and hopes about climate change were best conveyed through my native language, ASL, in my own words. My video allowed the audience to see the face behind the voice and to see that in addition to being a scientist, I am also an ordinary citizen who cares about our living planet.

“When you’re underwater, the sea does not discriminate,” said Ras Adiba Radzi, a diver who had overcome personal challenges. It is my passion to create an equivalent atmosphere above the sea, to make information and communication accessible anytime and anywhere. Language is not trivial. It is a powerful catalyst, turning thought into progress. It allows us to communicate, grow, and change together as a society.

Communicating so that all may understand – be it in ASL or in any other language, academically or conversationally – allows audiences to keep pace with changes to society and the environment. Communication about science empowers individuals and gives them an opportunity to become informed about the life surrounding them. It is a tool that allows for a sense of personal responsibility in each and every one of us and for the initiative to get involved in sustaining our beautiful home.