Fifteen years ago, I sat in Jane Lubchenco’s office at Oregon State University asking for career advice. Jane’s office is a reflection of her – full of accomplishments and warmth. There are stacks (and I mean STACKS) of manuscripts and journals around the office, awards both on the walls and piled up on top of each other, pictures of her family (by blood and by lab genealogy), and keepsakes from Africa to the Arctic. Even though Jane’s reputation intimidated me (and still does), she was warm and welcoming (and still is).

I wiped my sweaty palms on my legs, took a deep breath, and said, “I would love your career advice.” Here was my privileged dilemma – I was considering two great job offers. I could accept a prestigious Knauss Fellowship in Washington D.C. for a year, or I could accept an advocacy position at an ocean conservation non-profit.

I asked Jane what she thought I should do. She listened intently to my rambling and reasoning. Then, of course, she asked a question. This is something that we teach at COMPASS – to listen; ask; listen; share. Even if you (especially if you) already have an opinion, listen first. Her question was simple: “What do you want to do?” After a heavy sigh, my response was: “I’m unsure exactly what IT is.” I went on to explain how I love science. How I love the environment. How I love to connect people and ideas, think big, and try new things. How my previous work experiences in Washington D.C. helped me understand the public policy process and culture – including the surprising lack of science at the table during decision-making. I didn’t feel like either of these job opportunities were the right choices for me. I wanted to find a way to bring in the science, but in a way that made it relevant to all these people, audiences and communities – policymakers, NGOs, the world… but where could I do that?

Jane said, “Let me tell you about this thing a few of us are starting called COMPASS.”

She explained the frustration she and other leaders in the science, communication, policy, and philanthropy worlds felt around the disconnect between scientists and the real world, especially on ocean issues. “What we know about how oceans work, how they are changing, and the benefits and consequences of those changes,” she explained, “is not reflected in how people think about oceans or in our policies and practices.” We went on to discuss how scientists were not well equipped to get out in the world and talk with people about what they know. In fact, sometimes they are even discouraged from doing so. We also discussed how there were not enough efforts to elevate knowledge instead of institutions – and how co-founder Vikki Spruill was working to address this in the social sector, and bringing her innovative thinking to science communication. COMPASS was born as an experiment – a way to help scientists fulfill their social contract. I wanted in.

I started with COMPASS that week. Four years later, I became the first Executive Director. And at the end of this year, I’ll be leaving, secure in the knowledge that COMPASS is stronger and more vital than ever.

That’s because over the past fifteen years our mission has only grown more needed and our work has only grown more impactful. Our vision and goal: to help more scientists to get out in the world and transform, frame and accelerate critical conversations about the environment. Our shared belief: that scientists should have a seat at the tables where public agendas about the environment are set and advanced, but they need help getting there and being effective once they are. Our core competencies: training scientists, and connecting scientists to influencers of the public discourse. Our amazing team: we all love science, and especially scientists. We care deeply about the environment. We want to make a difference. We thrive on thinking big, making connections, and generously supporting others.

We found our ‘special sauce’ in our collective experiences in policy, science, media and communication, which blend together to inform our work and help us achieve our mission. We continue to tweak and update our recipe – evolving and changing in response to the world around us. And, wow, the world certainly has changed. We used to have to motivate scientists to get out into the world. Now, scientists want to engage. The research about science communication has exploded. New media channels are dismantling old information sources. The political pendulum has swung back and forth, and players have come and gone. And our environmental challenges – from climate change to water availability to ocean acidification – have become more urgent.

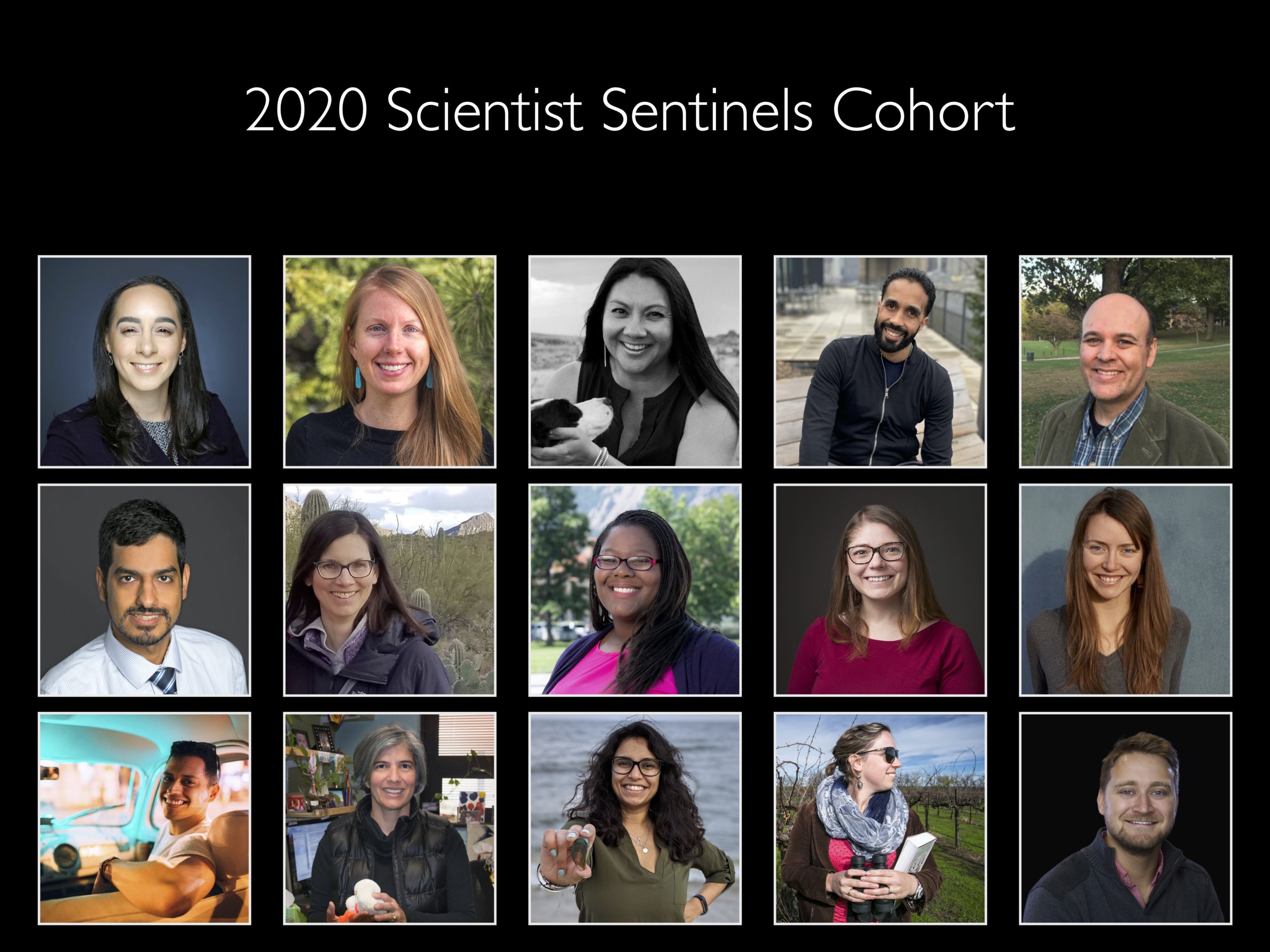

In response to these changes, we expanded our scope beyond ocean science to include water, fire, climate, energy, ecosystem services and other scientific topics about the environment. We developed ways to help scientists and journalists meet and learn from each other. We pioneered new ways to reframe scientific conferences to be more relevant to the world, by hosting journalist fellowships or including policymakers as part of these conferences. We’ve created space for scientists and policymakers – from the White House, to Congress, to state legislatures – to share, discuss, and learn from each other. We’ve created communities of confident scientists prepared to engage around topics like fire, ocean acidification, or marine protected areas. And with partners like the Leopold Leadership Program, the Switzer Fellows, the Wilburforce Fellowship and others, we’ve empowered new cohorts of scientist leaders.

As we navigated the rules of scientific engagement, our organization evolved too. We began as a project incubated at Island Press and then SeaWeb. We started with a single funder, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, that not only shared our vision, but was willing to invest in the long term to give us space to try, learn, and grow. Now, we are an independent 501(c)(3) non-profit with a diversified revenue portfolio, including both foundation grants and earned revenue. Our budget grows each year. We’ve built a strong operational, financial and administrative base, ensuring that our inter-disciplinary team is supported to do its great work.

We teach a lot of things in our training sessions; one important lesson we teach scientists is to push themselves to a place of discomfort – that’s where we all learn and grow. So, after 15 years at COMPASS, I’m taking our own advice – and pushing myself to a place of discomfort. My decision to step down from COMPASS at the end of this year was a hard one and an emotional one. In some ways, I could happily stay at COMPASS forever – the people, mission and work embody that hard-to-define “IT” that I was searching for in Jane’s office years ago. Being able to leave an organization during a time of strength is all too rare. I’ve learned it takes strength to do it. I’m proud to have been part of building and defining what this experiment has turned into. Some recent personal events, though, have starkly reminded me that life is short. I believe in new experiences; there’s still much for me to learn, try, and do.

Someone recently said to me, “I can’t imagine COMPASS without Brooke.” I can, without hesitation. COMPASS is stronger and more needed than ever. The opportunities for continued success and growth are enormous. The team is a remarkable collection of intelligent, innovative, and passionate people. We get more requests for our services than we can handle. We have ideas and opportunities waiting to be pursued. We have money in the bank and committed donors. Our board – a remarkable combination of scientists, communicators, and political appointees (Democrats AND Republicans) – is engaged and ready to help COMPASS transition to its next leader. I can imagine COMPASS without Brooke, but it’s a bit harder for me to imagine a Brooke without COMPASS. I’m both nervous and excited (“nerve-cited” as we say at COMPASS) to figure out what that looks like.

My first order of business will be to give my husband and two amazing daughters, who have had to share me with COMPASS for many years, my full attention over the holidays and the New Year. But after that? Much like fifteen years ago, I don’t know exactly what “IT” is – but I know it’s going to continue to be about my love for science and scientists, connecting them to society, facilitating changes that allow for more scientists to engage, and working toward a world where both environment and society can thrive.